왕열 展

『 K I A F 』

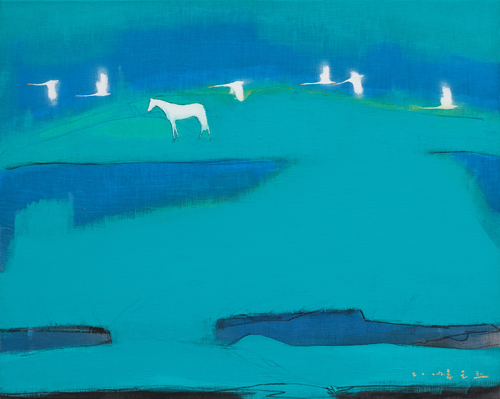

신무릉도원_140x140cm_파초,천에먹,아크릴

COEX

화랑 : 백송화랑 | 부스 : NO A-15

2010. 9. 9(목) ▶ 2010. 9. 13(월)

VIP Open : 2010. 9. 8(수) PM 3:00

서울 강남구 삼성동 COEX

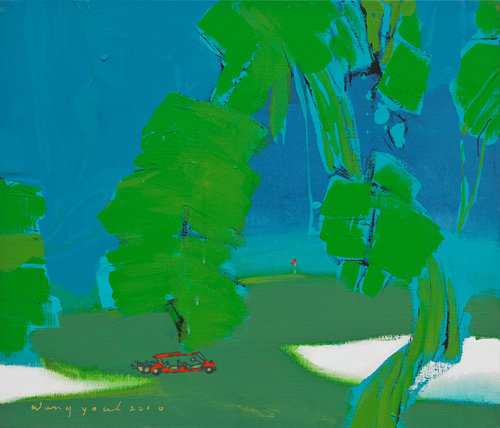

신무릉도원_73x60.5cm_동행,천에먹,아크릴 | 신무릉도원_73x60.5cm_동행,천에먹,아크릴

Wang Yeul’s Exploration of ‘Deconstructed’ or ‘Fused’ Landscape Paintings

By Oh Se-kwon, Art Critic & Daejin University Professor

1.

Traditionalism, contemporaneousness, and experimentation are the three pillars in Korean painting that have been profusely debated about recently in order to find appropriate solutions for these problems. However, these problems still remain to be solved and finding the answer seems difficult, despite constant discussions. As a result, we feel Korean painting remains outdated, compared to Western painting.

Some argue that its identity and even the term, “Korean painting,” is behind the times and should be replaced with just “painting” or “two-dimensional work.” This assertion may be true. While Western art underwent a rapid transformation and Western painters came to work freely in a wide variety of mediums including video, installation, performance, and photography, Korean painters confined themselves to a limited area, sticking to just traditional materials and subject matter. So, where do we go from here? We have to continue our studies and discussions to attempt a solution to these difficult issues.

Since the late 1980s when Post-modernism flowed into the Korean art world, a mixed use of Western painting methods in Korean painting temporarily seemed to solve a former stagnant state, but it also made its identity more ambiguous. Recently, however, Korean painting has begun to articulate its own distinctive characteristics separate from those of Western painting.

Korean artists embraced animation or cartoon-like expressions amid a Neo-Pop movement after the turn of the century, which can be regarded positive in that it became a motivation for new change. Korean painting recently underwent another shift in direction away from more traditional forms of expression. Now, artists are attempting to create new styles of landscape paintings through ‘deconstruction’ and ‘fusion.’ These new styles are thought to be more liberal and implicative than before.

신무릉도원_91x72.8cm_동행,천에먹,아크릴

2.

Wang Yeul’s art world can be discussed in many ways and approached from a variety of different angles. Here, I would like to briefly discuss several features of his art.

Deconstructed or Fused Landscape Paintings

In 1910 when Japanese colonial rule commenced, traditional Korean painting was blended with idealistic Chinese art, new Japanese techniques, and Western painting styles. Japanese painting style, however, became gradually dominant in the Korean art scene. Around 1919 when last court painters, Cho Seok-jin and Ahn Joong-sik passed away, Joseon’s court painting came to an end. They led the establishment of the Institute of Calligraphy and Painting, and maintained their influence through artists who studied there. They are still influential today and become a basis for the tradition of Korean painting.

After going through Japanese colonial rule, liberation, and the Korean War, Korean landscape painting underwent a gradual change in about 10-year cycles. In the 1950s and 1960s Korean painting broke away from the remnants of Japanese colonization. In this period outstanding artists like Lee Sang-beom and Byun Gwan-sik gained a firm foothold in the Korean Art world, establishing modern Korea’s true-view landscape painting style by cherishing the tradition of Joseon painting like Jung Seon’s.

In the 1970s Lee Young-chan, Ha Tae-jin, Kim dong-soo, Jung Ha-gyeong, and Cho Pyung-hui, influenced by then Western painting’s realistic style, began drawing their surrounding sights. This period is regarded as the period of the settlement of modern Korean landscape painting. In the 1980s when the ink and water painting movement started, Song Soo-nam, Lee Cheol-ryang, Shin San-ok, and Moon Bong-seon initiated a new tendency that blended natural scenery with urbanscapes. It can be referred to as the period of ink landscape and cityscape. Park Dae-sung, Oh Yong-gil, Lee Seon-woo, and Kim Moon-sik were active from the mid-1980s up to the 1990s. They worked in realistic landscapes, bringing on-spot scenery into their work.

신무릉도원_61x73cm_동행,천에먹,아크릴 | 신무릉도원_61x73cm_동행,천에먹,아크릴

With the introduction of liberal brushwork, new materials, and a more imaginative form of representation in the 2000s, a new tendency towards “deconstructed landscapes” or “fused landscapes” emerged. This new style of Korean landscape painting employs liberal expressions disregarding conventional brush work and makes use of Western materials like acrylic, going beyond traditional media. The reinterpretation of conventional landscapes or the incorporation of natural landscape scenery into everyday scenes of modern, consumer capitalist society are also important features. Works by Park Byung-chun, Wang Yeul, Lee Gu-yong, Kim Bom, and Kim Bum-seok show this tendency well and appear obviously different from the existing forms of conventional landscape paintings.

Wang Yeul deconstructs traditional landscapes, embracing and reinterpreting some of its distinctive elements. He employs mixed mediums such as acrylic, gesso, gold dust, silver dust, and varnish, as well as cloth-based ink. He maximizes the effects of conventional brush lines on a background applied with these mixed materials. He reproduces Korea’s traditional landscape paintings on a red or blue background. This expressive technique is rather similar with that of traditional Taenghwa (hanging Buddhist paintings), such as Guem-taenghwa (golden hanging Buddhist painting) and Hong-taenghwa (reddish hanging Buddhist painting), but departs from these forms and shows the viewer a newly interpreted version.

Wang represents the landscape’s mass, dimension, light, shade, and falling waterfalls intensely using black, gray or gold on a background applied with red or blue acrylic paint. As its background is acrylic, the Balmuk (various ink effects created by controlling the ink tonality and wetness of the brush) and Pamuk (a technique of applying dark ink first to a canvas and then spreading it to make the color lighter and create shading) effects of traditional Korean paper are rarely found. The use bright, highly-saturated red or blue tones gives off a fresh, exceptional effect. The implicit effects of condensation and perspective usually derived from empty white space are, in fact, also found in the red or blue blank spaces.

Wang’s deconstructive, fusion-like expression can be attained only after thoroughly practicing traditional landscape techniques using traditional paper and ink. Wang experiments with the effects of new types of line delineation using new materials, while still basing his work on conventional Eastern landscape painting. Up to this point, he has presented new forms and materials, but now I believe he has to make an attempt at pursuing new contents as well.

신무릉도원_46x53cm_파초,천에먹,아크릴

The Bird

The bird, Wang’s symbolic subject matter, has appeared regularly in his works since the Wintering series which features a city’s back alley corners. “At first, I arranged a bird for composition, but later it played a crucial role in my work. The bird became central and others were secondary in my work. As a symbol, many interpret it diversely. It is now at the center of my work.” Wang said.

The bird laughs brightly or weeps in sorrow. It flies alone or in pairs. It stands absently or dances buoyantly. All viewers may feel the bird is a symbol of a human being. His landscapes are not merely the description of natural scenery but the metaphoric representation of life aspects. Although the bird appears as a symbolic strength, it is essentially to represent urban dweller’s happiness, solitude, companion, and their various lives full of joy, anger, sorrow, and pleasure.

In the early 2000s, however, I recommended he should rid of birds in his paintings in order to step forward to a new direction. Whenever I presented such opinion, he expressed his sympathy, but said that ridding of the bird is not easy because it wriggled desperately. He is perhaps more impatient than me as he feels the need to remove it from his painting urgently, but now the matter will be solved with time.

신무릉도원_73x61cm_동행,천에먹,아크릴

Experimentation

Wang’s experiments have corresponded to each period’s traits in Korean painting. He made efforts to express the traditional in a contemporary feel, always pursuing something new. In his early days from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s, Wang Yeul executed the Wintering series, focusing on the features of ink painting in vogue at that time. He captured urban corners and seascapes in ink, evoking Balmuk and Pamuk effects. In the mid-1990s he began working in ink painting, which reflected a trend at those days. In this period he also experimented FRP reproductions of huge rocks in which marks of time appeared, as if in an old man’s wrinkled face. These experimental pieces were epochal at that time.

In the early 2000s Wang Yeul employed separated canvases, overlapping various images one another or juxtaposing concrete figures with abstract forms in various modes. In the mid-2000s he worked with cloth and acrylic, instead of Hanji and ink. As mentioned above, he attempts deconstructed or fused landscapes.

As indicated above, we can know that Wang is an artist who has tirelessly sought and experimented new forms. Wang is prompt in his practice and action without clinging to one result only and always pursuing a new objective.

신무릉도원_140x140cm_파초,천에먹,아크릴

3.

Since the early 2000s when Wang’s studio was at Sinsoo-dong, Seoul, I have frequently visited this place. Large canvases were here and there in his studio. I felt then that he was a prolific artist who completed his work promptly. I often noticed an empty canvas turned to an almost completed work in a night.

When he moved to Sinbong-dong valley, Yongin, I visited there more frequently as it was near my house. Whenever I visited there, he appeared to be totally absorbed in his task. After working and achieving lots of projects there for four years, he moved again to Gogiri valley near the Pangyo new town. It is not long, but he already did a number of works. In a word, he is an industrious artist.

An artist usually feels happiness when he can continue his work and experiments as well. Regardless of the sale of works, he stretches what he studied and thought to the full. Wang enjoys such happiness all. As one of his acquaintances, I expect his consistent efforts will come to fruition.

■ 왕 열 (Wang Yeul)

홍익대학교 미술대학 및 대학원 동양화과 졸업 | 홍익대학교 대학원 미술학 박사

개인전 | 38회 (중국, 일본, 독일, 스위스, 미국, 프랑스 등)

동아미술제 동아미술상 수상(동아일보사) | 대한민국미술대전 특선 3회(국립현대미술관) | 대한민국미술대전 심사위원 역임 | 한국미술작가대상 (한국미술작가대상 운영위원회) | 단체전 400여회

작품소장 | 국립현대미술관 | 경기도미술관 | 대전시립미술관 | 미술은행 | 성남아트센터 | 성곡미술관 | 홍익대학교 현대미술관 | 고려대학교 박물관 | 워커힐 미술관 | 갤러리 상 | 한국해외홍보처 | 한국은행 | 동양그룹 | 경기도 박물관 | 한국종합예술학교 | 단국대학교 | 카톨릭대학교 | 채석강 유스호스텔

현재 | 단국대학교 예술대학 동양화과 교수

Homepage | https://www.wangyeul.com

vol.20100909-왕열 展